Canon Kelly's Story

I was transferred to Bath on 12th July 1940. In that first year at Bath, there were between 300 - 400 air raid alerts. We were so close to Bristol, only ten miles across the valley, that every time the planes came across for Bristol, we had an alert in Bath.

The night the church was hit I slept through the alert, because we'd had a raid the previous night. Somebody had to come and call me, even though the siren was just on the corner of the building! We had become so blasé about alerts, that even though we'd had one attack, it didn't really register as something terrible. In that raid we had a very bad time. I can remember vividly hearing the bombers going out, and then turning to come in for their run, and then the bombs being released.

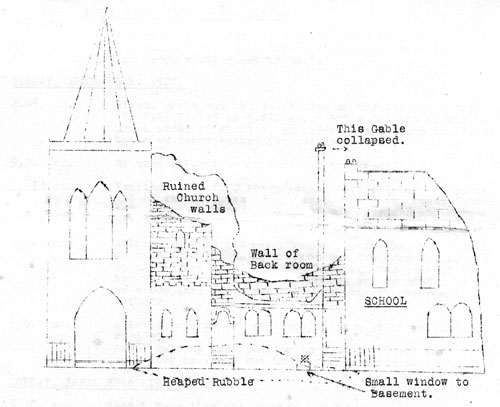

We had a direct hit on the presbytery - a big three-storey building, with a basement - and we had heard the whirr of this bomb coming down. A priest and I were watching for incendiaries at a presbytery window that looked out onto the back, and onto the roof of the church. He was standing at the window, and I was standing beside him, just clear of a cross passage that ran between us from the presbytery into the church.

We had a direct hit on the presbytery - a big three-storey building, with a basement - and we had heard the whirr of this bomb coming down. A priest and I were watching for incendiaries at a presbytery window that looked out onto the back, and onto the roof of the church. He was standing at the window, and I was standing beside him, just clear of a cross passage that ran between us from the presbytery into the church.

When the bomb hit, the top two stories of the building caved in, and the priest next to me vanished with the rubble into the basement. My tin hat was peppered with glass from the window, but I had been sheltered from the collapse by the porch of the passage. A woman and her daughter who had come in for shelter had thought the basement would be the safest place, and they were also buried.

We had a fire fighting team, made up of a very big contingent of Irishmen who were working at an underground munitions factory, built by MacAlpine, at Corsham. Many of them were lodging at Bath. They had a bad reputation for drinking and rowdy behaviour, yet a number of them used to come to St John's to worship. It was in fact an extraordinary sight, because the church holds 500, but when they came we had to find extra chairs. It was a tremendous congregation of big men!

The parish priest and an Irishman who had also been looking out for incendiaries came running around to the front of the church. They saw the total destruction, and couldn't believe that anyone would still be alive. The priest called out "Anybody. there?" And he told me of his great relief when I answered "yes..."

The parish priest and an Irishman who had also been looking out for incendiaries came running around to the front of the church. They saw the total destruction, and couldn't believe that anyone would still be alive. The priest called out "Anybody. there?" And he told me of his great relief when I answered "yes..."

The Irishman with the priest was called Jim McLaughlin, from Donegal. He'd been lodging nearby, and his house had been destroyed during the first night of the raids. He had a sister working in Swindon, and had come down to the railway station to stay with her for the night. But then it had occurred to him that there might not be enough fire watchers, and he left the platform and came down to us. It really should go into the record, what he did. He was a steel erector, and I think the strongest man I ever met. We wanted to try and find Father Sheridan who had been buried, and the people in the basement. We came down the stairs to the basement, and at the bottom was a door blocked by the debris. Jim literally took the door apart in his hands.

Within about half an hour we had found Father Sheridan buried, and dead, of course. We realised that the mother and daughter sheltering in the basement kitchen were dead as well.

We really didn't know what to do, and thought that we should tell the police - although what we expected the police to do, I don't know. The raid was still on. I went into the police station and met this young policeman, and told him the situation. He said, "Well, I'll have to have that in writing!" So I said he'd have to put up with just a verbal report. Then he saw I was bleeding from a little cut in my leg, and said I'd have to go into hospital for an anti-tetanus injection. I said I'd just escaped with my life and would take my chances...

I went back and we stood in the forecourt of the church, watching the planes firing tracer bullets. We thought they were ours, but discovered later that they were German planes. Next day they found one man with his head cut clean off by bullets. What had misled us was the fact that there was a night-fighter station out at Colerne, and we thought that our planes had taken off. But it happened that that weekend there was a transfer of personnel, and there was nobody there. Bath had no anti-aircraft cover that night, so the German planes had an uninterrupted time of it, and strafed the place.

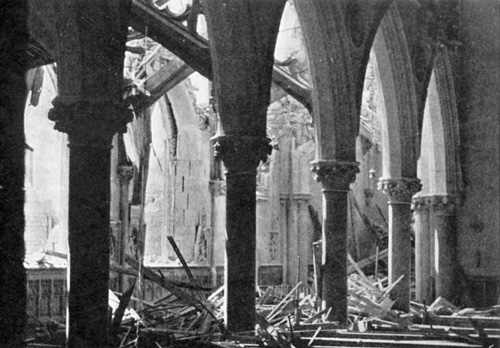

That was 27th April, 1942. The bombing brought the priests and the people closer together. The bomb had taken the roof off the church, so where were we going to hold our services? Now in the First World War, the convent built some temporary classrooms. And because Bath was subject to floods at that time, with the waters reaching the convent, these temporary classrooms were put on stilts - seven feet high. And this created an enormous space underneath, which became what we called our "basilica" where we had mass.

By the following Sunday after the Blitz this area had been organised. It was interesting for the priest because there were no walls, and you would be bellowing to be heard by those at the edges of the area, while those in front were deafened! In the following weeks we closed this area in with timber, and this became our church for at least 12 months.

The priest appealed to the Irishmen at mass to come and clear out the masonry which had fallen into the church. There were about 100 of them that set to work after mass some of them didn't even bother to go home and change. They came in their Sunday best! And they worked until dark, and the following day as well - they took the day off work. They stacked the stones in the forecourt. Afterwards, when the firm came to repair the church and looked at what had been done, they said it would have taken them six weeks, with all their resources, to do what those Irishmen had done in a few days. This had a very interesting consequence. There was no building allowed during the war, but when the authorities came to inspect the damage, and saw the work that had been done by volunteers, they said, "These people deserve to have their church." And we were allowed to re-roof it, even during the war.

Exactly a year later, on 26th April 1943, I remembered in my mass the people who had lost their lives on that anniversary. That night before going to bed I was thinking about the blitz, and I later woke up with a nightmare. I looked at my watch, and it was ten to two, which was the exact time that the bomb had struck. We knew that was the time, because the church clock in the tower had stopped at exactly that time, and stood at ten to two for a couple of years. That was eerie...

Comment

Canon Kelly met some of the project members in the early days of the project, and related his story. That same story can be seen (a longer version but without our illustrations) in "THE WEST COUNTRY AT WAR" by Lucinda Hersey & Catherine Mason. Details are on our Books Page

If you can't find where you want to go next using the navigation buttons at the top of this page, this button will take you to the page containing the complete site index.