The Auxiliary Units

ORIGINS

As soon as it became apparent to Churchill that Hitler might launch an invasion of Britain after Dunkirk, urgent thought had to be given to every aspect of home defence. Boer Commandos taught the British the value of units that operated behind the enemy's frontline and were able to melt into their surroundings after they had attacked. Indeed, in the dark days following Dunkirk, Lieutenant Colonel Dudley Clarke RE, a South African who had been weaned on the exploits of the Boer Commandos had written a paper for Churchill and the War Cabinet in which he recommended the adoption of Boer tactics. This led to a serious consideration for a stay-behind resistance force, that would slow down advancing enemy troops and grant the regular army time to mount a counter-attack.

On 30 June 1940, Churchill invited General Thorne, one of his military advisors, to come to lunch at Chequers. That lunch at Chequers was to have even more far-reaching effects, for it revived an idea that General Thorne had first considered years before: the formation of a 'stay behind' guerrilla resistance force in Britain. They were not expected to count for much in direct combat with a superior invader, but since they had intimate knowledge of their terrain, and could be provided with stockpiled secret arms caches, they were reckoned to present an obstacle out of all proportion to their strength.

Major Gubbins (later to become Sir Colin Gubbins and to achieve fame as the head of SOE, (and pictured right), on his return to Britain from Norway in June 1940, was promoted to Colonel, and was instructed to create an underground army which would form the nucleus of a resistance movement in the event of a successful occupation of all or part of the UK by German invasion forces. This organisation was to be known by the codename of 'Auxiliary Units' and was to come under the direction of GHQ Home Forces, whose Commander in Chief, at that time was Field Marshal lronside.

Major Gubbins (later to become Sir Colin Gubbins and to achieve fame as the head of SOE, (and pictured right), on his return to Britain from Norway in June 1940, was promoted to Colonel, and was instructed to create an underground army which would form the nucleus of a resistance movement in the event of a successful occupation of all or part of the UK by German invasion forces. This organisation was to be known by the codename of 'Auxiliary Units' and was to come under the direction of GHQ Home Forces, whose Commander in Chief, at that time was Field Marshal lronside.

Initially Colonel Gubbins requested and was given the support of some dozen officers, hand-picked from those known personally to him and on whom he could rely to 'get on with the job'. These were known vaguely as 'Intelligence Officers' and were to form the Regular Army units who were to be responsible for the organisation and local training of the proposed resistance movement.

In 1940, Peter Fleming (the brother of James Bond author Ian Fleming) was working for Military Intelligence (Research) - normally abbreviated to M.I.(R) - a semi-secret department within the War Office. M.I.(R) considered Fleming to be the best candidate to establish a British guerrilla unit, in particular one that would be comprised of men who could live off the land. So in a secluded farmhouse called the Garth in Bilting, Kent, Fleming set up the first regional training centre for a new, British, 'stay-behind' force. This, the first "Auxiliary Unit" was known by the cover name 'XII Corps Observation Unit'. The name Auxiliary was chosen because it was thought a suitably nondescript term that was unlikely to arouse unnecessary attention.

Intelligence suggested that, although the Germans might supplement their invasion attempt by the use of airborne forces, the main assault would be seaborne and might occur anywhere in the approximately 300 miles between the Norfolk and Hampshire coasts. Kent was considered the likeliest invasion area. The second most likely was East Anglia, and here, using Fleming's unit as a model, a similar organisation was set up. Then a third, in Sussex, around Lewes and Arundel, did likewise. By the end of August 1940 the Auxiliary Unit organisation stretched as far north as Brechin on Scotland's cast coast, south to Land's End and north of the Bristol Channel as far as Pembroke Dock.

M.I.(R) however, felt that the entire British coastline stretching from southern Wales eastwards round to Scotland was vulnerable and Auxiliary Unit patrols should deployed throughout this region accordingly. The best units were concentrated in southern England near the coast. In this way Auxiliary Units could be put to good use scouting and spotting areas the Nazis might use to expand a particular bridgehead as they began their inland push.

Strictly speaking a Unit is a composite thing, embracing location, weaponry and personnel. However, Auxiliary Units chose their own base location and often improvised weaponry, so post-war information often treats Units as personnel, and I have also used that simplification where convenient.

A member of the Auxiliary Units in Bath has sent me his memories of recruitment, training and exercises. He described himself as a member of the Bath Resistance Movement. I have placed it in the Memories section.

Auxiliary Unit sabotage missions would have had the effect of slowing down this build-up, buying time for the regular army to reach peak efficiency, and be deployed directly against the most threatened area. Eventually there were patrols all over the UK extending inland as far as Manchester and Hereford, and by late 1941 nearly 600 had been formed, comprising over 3,500 Auxiliaries.

Auxiliary Units comprised two parts. The first consisted of specially selected civilians with a good knowledge of their local area and physically capable of living rough and fighting and harassing enemy forces. The other part consisted of local wireless networks operated by Royal Corps of Signals personnel with outstations near the coast, each having a civilian operator. A system of spies and runners would supply information of enemy activity to these operators for relaying to the Signals control stations who would in turn transmit the information to the Area HQs attached to Brigade/Corps of the conventional forces. Each control station had from five to ten outstations, Southern England having a larger number as the more likely area to be invaded.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Because the Auxiliary Units were intended to operate behind enemy lines after an invasion, when Government offices and military bases had been captured, it was important that the enemy should find nothing in captured files that could alert them to the existence of a resistance organisation. Almost nothing was written down, which means that this part of wartime history can now only be pieced together from personal memories.

As well as the overriding need for secrecy, the Auxiliary Units were expected to improvise, and so there would be differences in individual experiences from unit to unit. Many of those involved will recognise most of what follows, but there could be differences in timescale and detail. It is written to be typical rather than definitive.

RECRUITING

The Auxiliaries (or "Auxiliers" as they were sometimes known) were all to be part-time volunteers, recruited mainly from members of the recently formed Home Guard, and Gubbins was given the authority to requisition suitable men. These recruits varied in age and occupation, from young students, factory workers in reserved occupations, miners and farmers, to professional men like doctors and accountants. Age was no barrier, as long as the recruit was fit and capable of existing under the harsh conditions anticipated. Gamekeepers and countrymen of all sorts were much sought after, as well as those with experience of Scouting and woodsmanship.

Although the battalion numbers were created in the early days, most members did not know these identities existed, and it was considerably later that insignia were produced and issued, and some areas, including Bath, never received them at all. To avoid looking conspicuous, patrols usually wore the badges of their "notional parent" Home Guard Unit when wearing uniform, but avoided being seen in public in uniform if possible, in case Home Guard members were suspicious.

The recruits were told that as far as the units they were drawn from were concerned, they were being selected for special Home Guard duties, although in reality the Auxiliary Units had their own command structure under MI6 which was completely different from that of the Home Guard. Recruits were notionally 'posted' to one of three battalions, later numbered 201 (Scotland and Northern Counties), 202 (Midlands) and 203 (London and Southern Counties). Whilst these men publicly maintained that they were in the Home Guard but on special duties (and indeed any that had actually been recruited from the Home Guard usually kept and wore their original Home Guard insignia), this was purely a cover.

Since they were not enrolled as fighting men, they were not strictly covered by the Geneva Convention, although their uniform may have given them some degree of protection against being shot out of hand if captured. As part of their Home Guard cover, Auxiliaries wore the standard 1940 pattern battle-dress blouse and trousers, with the FS sidecap. The trousers were tucked into black or dark brown leather anklets over standard black ammunition boots. No equipment was worn, other than a webbing or leather waist belt, supporting a revolver holster.

As a concession to the 'dirty' conditions under which Auxiliary Units operated, either in training or more commonly, in the construction of their underground 'hideouts', they were given Overalls, Denim, comprising a separate blouse and trousers, worn over and to protect either their uniform or civilian clothing, together with black rubber short lace up boots having a waterproof tongue behind the lace eyelets. These were ideal for construction work or for moving soundlessly over paved surfaces. The rubberised brown groundsheet/cape was also issued and some units wore a woollen 'cap-comforter' with their denims.

This was the official position. In practice however, lapel badges were issued after the "Stand Down" at the end of 1944, and were presented by local area Intelligence Officers. It is thought that MI6 arranged it, but no records survive to prove or disprove this.

Insignia were minimal, the cap badge being that of the county regiment. The Home Guard shoulder title was worn on each shoulder, surmounting the battalion number and the county name or abbreviation, both in black on khaki denim patches. Off duty, members could be identified by a small metal lapel badge (pictured), bearing the three battalion numbers, in cross formation on the red and blue shield and crown of GHQ Home Forces. Some Auxiliaries wore better quality Army issue uniforms 'acquired' from friends or relatives in the Forces.

Insignia were minimal, the cap badge being that of the county regiment. The Home Guard shoulder title was worn on each shoulder, surmounting the battalion number and the county name or abbreviation, both in black on khaki denim patches. Off duty, members could be identified by a small metal lapel badge (pictured), bearing the three battalion numbers, in cross formation on the red and blue shield and crown of GHQ Home Forces. Some Auxiliaries wore better quality Army issue uniforms 'acquired' from friends or relatives in the Forces.

Likely recruits were vetted before being approached. Vetting was done by plain clothes or Special Branch police officers who made discreet enquiries from employers or neighbours without knowing or stating the purpose of the enquiry. Once recruited, volunteers were subject to the Official Secrets Act, and their wives and families were largely unaware of the special duties in which they were involved.

The movement was organised on the cell principle, the cell being a patrol of some five or six men led by a sergeant. A volunteer Group Leader, given the rank of a Home Guard Lieutenant or Captain, would be responsible for several such patrols within a ten or fifteen mile radius of his home, and certainly in the early days, this was the only contact between individual patrols. By September 1940, most counties had their own Intelligence Officer, who was often stationed in his home county because of his contacts. Each Intelligence officer was given a platoon of some dozen NCOs and men, to help him with the supervision, distribution of supplies to and local training of the Auxiliary Unit patrols in his area.

TRAINING

TRAINING

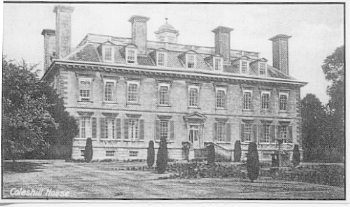

In June 1940 the selection and training of the patrol members began in earnest. Col. Andrew Croft was appointed as operational and training officer, and by the following November Croft had trained 24 seven- or eight-man groups in Essex and Suffolk. Croft then opted to return to Commando units, and the Auxiliary Units HQ and training centre moved to Coleshill House (pictured right), a Palladian mansion about 10 miles from Swindon, chosen by Colonel Gubbins because its large parklands and woods made it very very suitable for guerrilla training.

Auxiliary Units were given high priority in the provision of patrol weapons and explosive devices. Personal weapons were, with some exceptions, intended for defence rather than offence, as in no way was it proposed that they should fight pitched battles with superior forces but rather should avoid direct confrontation, killing only when necessary to achieve surprise or to effect material damage on the enemy's supply lines or stores. Explosives were to be the main offensive weapons of the Auxiliary Units, whose role was to attack the enemy's stores, transport and communications rather than his ground troops. But given the right sort of combustible target, a properly placed incendiary could do as much, if not more, damage to an enemy's stores and supplies as an explosive, and the Auxiliary Units were supplied with a variety of equipment for this purpose, which could be used, either on its own or in conjunction with explosives for greater effect. Every Auxiliary received training in the basic principles of making and using explosive and incendiary devices.

Thus patrols and individual Auxiliaries were sent to Coleshill for training in the use of explosives, sabotage, booby-traps and unarmed combat. Instruction in the latter was based on a book by W.E. Fairburn, designer of the Fairburn dagger (Field Service Fighting Knife). Having been a policeman in the seamier areas of Shanghai, Fairburn could write with authority on all the dirty tricks that could be employed in close combat, as well as on the art of silent killing. How well patrols had learned their training was thoroughly tested, often with patrols competing against each other. These tests were a combination of tests of knowledge and tests of effectiveness.

Thus patrols and individual Auxiliaries were sent to Coleshill for training in the use of explosives, sabotage, booby-traps and unarmed combat. Instruction in the latter was based on a book by W.E. Fairburn, designer of the Fairburn dagger (Field Service Fighting Knife). Having been a policeman in the seamier areas of Shanghai, Fairburn could write with authority on all the dirty tricks that could be employed in close combat, as well as on the art of silent killing. How well patrols had learned their training was thoroughly tested, often with patrols competing against each other. These tests were a combination of tests of knowledge and tests of effectiveness.

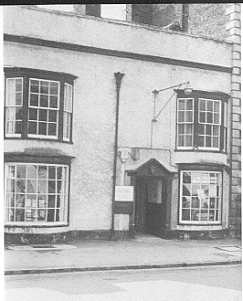

Secrecy was such that trainees did not report to Coleshill direct. They were instructed to call at the tiny post office in Highworth, where, on proof of their identity, the post-mistress would leave them, make a short phone call, and then advise them that transport was being sent to collect them.

Secrecy was such that trainees did not report to Coleshill direct. They were instructed to call at the tiny post office in Highworth, where, on proof of their identity, the post-mistress would leave them, make a short phone call, and then advise them that transport was being sent to collect them.

Initial training was given by the Regular Army support troops, and such knowledge was passed on largely by word of mouth, and in the interests of security, no written training manuals were prepared. However, in July 1942, membership of the Auxiliary Units had grown to such an extent that some form of essential sabotage information was necessary as an aide-memoire for the volunteers. This was issued as a 42-page booklet, put together by a captain in the RE and which contained all the reminders that a well trained saboteur would need in practice. Apart from the standard government caution relating to the disclosure of information to unauthorised persons printed on the fly-leaf, there was no indication for whom this publication was intended.

As a doubtful concession to security, it was given a cover title which would not look out of place on any farmer's bookshelf, The Countryman's Diary - 1939. It was humorously issued 'With the Compliments of Highworth and Co' and stated that 'Highworth Fertilisers do their stuff unseen, until you see results!' This could well have become the operational motto of the three Auxiliary Unit Battalions!

LATER YEARS

Once the German plans for an early invasion of Britain had been deferred, the immediate need for Auxiliary Units had passed, and they were able to concentrate on the construction of their permanent bases, training and the acquisition of their weapons and explosives.

Local training largely took place at night, the patrols moving silently about their area, learning its characteristics and byways and practising the arts of demolition on tree trunks, abandoned railway tracks and derelict vehicles. Any 'nasty sounds of banging' were attributed by the local population to stray enemy aircraft discharging their bomb load before returning home.

Patrols also participated in group training and frequently assisted the Military in 'their areas with exercises or 'schemes', often playing their intended roles of saboteurs or guerrillas.

As 1944 approached the threat of invasion receded, although the patrols were maintained in a state of readiness. Gradually, some of their stores, particularly Plastic High Explosive and delay mechanisms were called in for use by the invasion troops or by the European Resistance. Meanwhile, the Intelligence Officers and their teams had been disbanded and posted to other units, many joining the SOE or SAS Regiment, where they applied their skills in clandestine operations in occupied Europe.

Yet it was considered that there was a possibility, albeit remote, that the Germans could mount a counter-invasion against southern England, and Auxiliary Units were alerted prior to D-Day. Some North Country patrols were moved to the Isle of Wight, which could have become a prime target, to increase the Auxiliary Unit presence there, and they carried out some preparatory work which, in the event, was not needed. Patrols in the south-west were also put on stand-by against a possible enemy air landing.

DISBANDING

By November 1944, the fighting on the Continent was sufficiently advanced for the Auxiliary Units to be stood down. Their weapons and explosives (some, not all) were collected, any doubtful explosives being carefully destroyed. In that month, most County battalions held a standing down parade in their County town, where they were they were addressed by their Colonel-Commandant and individually presented with 'Home Guard' certificates (although they were still not members). When Defence Medals were issued to members of the Home Forces, Auxiliaries were overlooked, as they still had no official standing.

Of greater personal value to the Auxiliaries were the letters sent to each of them which confirmed and emphasised the secret nature of their duties. What had begun in secrecy ended in secrecy, and it was not until April 1945 that the existence of the British Resistance Movement was released to the Press.

CONCLUSION

A member of the Auxiliary Units in Bath has sent me his memories of recruitment, training and exercises. He described himself as a member of the Bath Resistance Movement. I have placed it in the Memories section.

Fortunately, it will never be known how effective the Auxiliary Units would have been in practice, but it is possible to speculate, based on the knowledge gained from the experiences of the European Resistance Movement. Certainly, Auxiliary Units had a head start on these, they were well organised, well trained and well supplied with the necessities for underground activities. It is generally considered that their effectiveness would have been high in comparison with their numbers, although the patrols themselves thought that their active life would not last longer than a few weeks.

Whilst casualties would have been serious and inevitable, there is no doubt that some members would have survived the initial actions and that these would either have gone to ground or returned unobtrusively to their homes, during the confusion of the early occupation. These men could have formed the nucleus of any National Resistance, acting as leaders to recruit and train the population as the harshness of the occupation became felt. Once the hidden stores of arms had been used up, patrols would have depended upon captured weapons. Like their European counterparts, any movement would have suffered from the activities of collaborators and informers, and all Auxiliaries were aware of the possible effect that their actions would have had on their families, friends and neighbours if reprisals were inflicted.

Additional Information

The Bath Garrison of the Home Guard had its headquarters in Number 15 Queen Square. There were two Bath battalions:

5th (Bath City) Battalion Somerset Home Guard, under the command of Lt. Col. G H Rogers.

6th (Admiralty) Battalion Somerset Home Guard, under the command of Lt. Col. D Morrison.

Intelligence officers were sent around the country to establish Auxiliary Units. Alan Crick was sent to Somerset and Dorset to organise Auxiliary Units there, and once formed, these Units were commanded by Captain Ian Fenwick, initially from a headquarters at 28 Monmouth Street, Bridgewater, but later moved to The Lodge, Bishop's Lydeard, near Taunton. Stores were held at Bishop's Lydeard.

There were five Auxiliary Unit patrols notionally attached to the 5th Battalion and another five notionally attached to the 6th.

Captain Shackell's command was not restricted to Bath, but included Norton St Philip, Radstock and Midsomer Norton. At the time of the "stand down" he was the area Intelligence Officer.

The five Bath City patrols were Swainswick, Bathampton, Weston, Englishcome and Southstoke. These patrols were commanded by Capt. Malcolm T. Shackell (Swainswick Patrol) and Lt. William Ralph Hornett.

- Swainswick Patrol

- This patrol had its hideout in the south corner of Bare Wood just below the Gloucester Road. The major objective for the patrol was Colerne airfield.

- Bathampton Patrol

- This patrol had its hideout in one of the stone mines on Hampton Rocks. The objectives for this patrol were the railway junction at Bathampton, and Claverton Manor if occupied by the Germans. Secondary areas for possible sabotage were the engine sheds at Green Park station and Colerne airfield. Besides its hideout the patrol had an arms/explosives store in what had been the explosives store of a disused quarry on the edge of Claverton Down, near the top of Widcombe Hill. This store was damaged in the raid of 26 April 1942 and its contents were then transferred to Manor Farm Swainswick.

- Weston Patrol

- This patrol had its hideout at the north end of a field called Long Pear Tree that is near Weston village, Bath.

- Englishcombe Patrol

- This patrol had its hideout in Kilkenny Wood (Middle Wood), Englishcombe. It was an Elephant Shelter (which was like a very large Anderson Shelter) buried in the bottom right hand corner of Middle Wood GR 727617, close to Kilkenny Cottages.

- Southstoke Patrol

- This patrol had its hideout at the bottom of Rowley Valley in Hodshill Wood. It was under the command of Captain M. Shackell.

When these patrols (all commanded by Capt. Malcolm T. Shackell) had to meet, they did so on neutral territory, at Mary's Gown Shop, 15 Milsom Street. There was a family connection to this unlikely venue: Sgt. J Giles of the Bathampton Patrol married the daughter of the owner.

The five Admiralty patrols were No.1 Kelston Park (Kelston), No.2 Langridge, No.3 Warminster Road, No. 4 Prior Park and No.5 Newton Park (Newton St.Loe). They were commanded by Captain Leonard Arthur Aves with Lt. Jeffery George Spearman and 2nd Lt. George Richard Hutchings and 2nd Lt. Ivor MacG Phillips were the other officers. (Lt. Spearman was later promoted to Captain)

- Admiralty No.1

- This patrol had its hideout at Kelston Park, in the Ice House at the top of the stone steps leading down into the wood.

- Admiralty No.2

- This patrol had its hideout just outside the village of Langridge, in the valley roughly half way between Upper Langridge Farm and Charlcome Grove Farm. The Royal Engineers completed this base in 1943.

- Admiralty No.3

- This patrol had its hideout off the Warminster Road in Hengrove Wood. Their base was located near the point where a stream descending from Hampton Rocks meets the bridle track from the Warminster Road to Claverton Manor. Water was supplied from the stream by a beer pump purchased from Bowlers in Bath. (This base was about 200 yards from the base of the Bathampton Patrol. The Bathampton Patrol knew of the Admiralty No 3 base, but there is no indication that the Admiralty No 3 patrol knew of the presence of the Bathampton Patrol).

- Admiralty No.4

- This patrol had its hideout in Prior Park. The icehouse in the grounds of Prior Park just north of the larger lake was their base. Today it can be identified from the path by the proximity of a Yew tree.

- Admiralty No.5

This patrol originally had its hideout the old mineshaft at Pennyquick but abandoned it because it tended to flood. The patrol then moved to a base in Newton Park. For transport the patrol acquired a large Canadian Essex Terraplane car that could accommodate seven persons. (There were several pre-war Hudson Essex Terraplane models; the picture is the one most capable of carrying seven.) L/Cpl S.F.Phillips was its custodian/driver.

This patrol originally had its hideout the old mineshaft at Pennyquick but abandoned it because it tended to flood. The patrol then moved to a base in Newton Park. For transport the patrol acquired a large Canadian Essex Terraplane car that could accommodate seven persons. (There were several pre-war Hudson Essex Terraplane models; the picture is the one most capable of carrying seven.) L/Cpl S.F.Phillips was its custodian/driver.

If you can't find where you want to go next using the navigation buttons at the top of this page, this button will take you to the page containing the complete site index.