The Third Attack

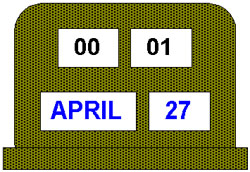

During the evening of April 26th a total of 83 bombers were prepared for operations and loaded with a total of about 100 tonnes of high explosive and nearly 8,000 incendiaries. Bath was again to be the target.

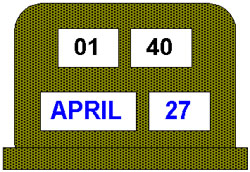

Just after midnight, 20 raiders were plotted taking to the air from Le Havre. These were followed shortly by others from Cherbourg, Dinard and St. Brieuc. 45 minutes later, 2 Hurricanes from Tangmere and 2 from Charmy Down, a wartime airfield just north-east of Bath, were sent on patrol along the south coast and another 10 from Charmy Down were instructed to intercept over Bath.

A Beaufighter from Middle Wallop near Salisbury successfully intercepted the first raider, an He III (pictured right), near Portland and damaged it causing it to turn and limp back to Avord airfield.

A Beaufighter from Middle Wallop near Salisbury successfully intercepted the first raider, an He III (pictured right), near Portland and damaged it causing it to turn and limp back to Avord airfield.

10 minutes later a Beaufighter attacked a Ju88 10 miles south of Exmouth and damaged it, forcing it to turn for home.

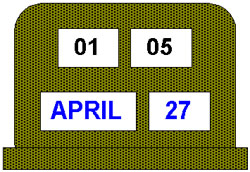

The first of the attacking aircraft arrived over Bath. This time the defences were better prepared: the air raid warning had sounded 10 minutes before the planes arrived, giving the residents time to seek shelter, and fighter aircraft were being scrambled at Colerne.

The first of the attacking aircraft arrived over Bath. This time the defences were better prepared: the air raid warning had sounded 10 minutes before the planes arrived, giving the residents time to seek shelter, and fighter aircraft were being scrambled at Colerne.

5 obsolescent but still serviceable Defiants (pictured right) took off just 5 minutes after the German bombers arrived, followed immediately by 2 Hurricanes.

Chandelier flares fell slowly through the air, giving off a lot of light while they fell, thus making the ground below more visible.

Incendiary bombs were quite small, weighing only a kilogram each. They fell quickly and burst into flames when they landed, setting fire to anything flammable that they landed on.

In clear moonlight conditions, the German bombers released chandelier flares and incendiaries, followed by the main attack on Bath which lasted for 40 minutes. Many of the bombers dived down to between 3000 and 4000 feet to deliver their high explosives across the city from south west to north east and back again in a southerly direction. Some of the attackers again machine-gunned the streets to hamper the emergency services.

The defending fighter planes started to engage the German bombers. A Dornier 17z was flying at 1500 - 2000 feet over Lansdown, machine-gunning the streets, when it was fired on by a Hurricane. The bomber was damaged and fled for the safety of France, but it crashed into the sea before it got there.

20 minutes later a Hurricane attacked a Dornier 217 over Bath and damaged it, and shortly afterwards, a Beaufighter attacked a Dornier 217 over the city.

A Defiant from 125 Squadron attacked one of the last bombers, an Heinkel that was flying at 4500 feet near Bristol. Although the Heinkel was damaged it managed to return to Rennes airfield.

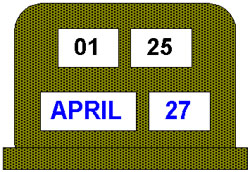

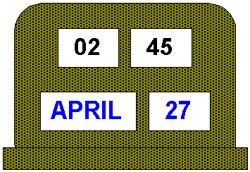

At 2:45am the "All Clear" sounded. Bath would not be bombed again for the rest of the war, but the residents of Bath could not know that at that time.

The raid was described soon afterwards on German radio - "In good visibility, a great number of high explosives and incendiary bombs were again dropped on the city. The bomber pilots could observe the excellent results of their bombing. Large fires broke out in all quarters, especially in the north".

War Office and Luftwaffe Archives

A local historian, John Penny, researched the RAF records and the Luftwaffe records that survived the war, and prepared a very detailed analysis of exactly what happened during the third attack.

After The Raid

Unlike the second raid the previous night, the bombers carried a high proportion of incendiaries, and the city was unprepared for that. There was also more wind than the night before, which fanned the flames once a fire took hold. Many of the firewatchers who should have been on duty failed to report to their posts. Some had been killed or injured the previous night; some had become trekkers; and some thought it was too dangerous and simply failed to turn up.

Dealing With Fires

A lot of houses had been left empty when families deserted the city, and any incendiaries that fell on their roofs created major fires because the doors were locked, and a small fire became a large fire before anybody thought that they should break in to deal with it.

To make matters worse, the high explosive bombs dropped were on average rather larger than the night before, and many water mains were damaged. Emergency storage tanks had been set up to cover a possible shortage of mains water, but in some areas the supplies proved insufficient for the number of fires burning.

One notable example was the Assembly Rooms (Pictured). Initially, the Fire Service had the blaze well under control, but then their water supplies ran out, and the fire took hold again, destroying most of the interior of the building.

One notable example was the Assembly Rooms (Pictured). Initially, the Fire Service had the blaze well under control, but then their water supplies ran out, and the fire took hold again, destroying most of the interior of the building.

The other consequence of the larger bombs was the sheer destructive force they brought. The death toll from the third raid was higher than from either of the previous two raids.

The firewatchers who had reported for duty saved many buildings, but the sheer number of fires overwhelmed the fire fighters at first. At least one of the fire-boats on the river had been sunk and was out of use. Bombs had damaged several water mains, and in the affected areas, only water in emergency tanks was available, and these did not take long to empty.

Fire Brigade reinforcements from Bristol came to help. Before the Bath blitz, Bath had not needed outside help for fire fighting. Indeed, Bath fire crews had frequently travelled to Bristol to help out there, but Bristol crews had not been needed in Bath before. Thus, they had little knowledge of the city apart from the main roads. When they arrived, they found that their natural route to Bath along the Upper Bristol Road was impassable: as well as the debris and rubble in the roadway, there was an unexploded bomb embedded in the middle of the road near the gas works. Being unfamiliar with the road layout, these outside crews lost a lot of time finding alternative routes to the fire stations they were to report to.

Once the outside fire crews had reported for duty, they often did not know where to find the fires to which they were sent, and they again lost time while messengers on bicycles or motorcycles, following instructions given to them by Civil Defence, guided them to their destination.

Once the outside fire crews had reported for duty, they often did not know where to find the fires to which they were sent, and they again lost time while messengers on bicycles or motorcycles, following instructions given to them by Civil Defence, guided them to their destination.

Often the shortest route was blocked by an unexploded bomb or rubble from wrecked buildings and another way had to be found.

The picture shows Kingsmead Street, which was one of the main routes between the city centre and the Upper Bristol Road in 1942. Even for agile pedestrians it was almost impassable.

Rescuing The Trapped

When the raid finished, it was the job of the Rescue Squads to find where people were alive but trapped in wrecked buildings, and to dig them out.

Rescue Squads had been trained to recognise how Bath's buildings were constructed and specially trained to work in collapsed buildings without bringing further rubble down on themselves and the survivors.

They started work as soon as the bombing ended. Rescue Squads also arrived from Bristol, but they were delayed, as the Bristol fire-fighters were, by blocked roads (by this time, bomb craters and rubble blocked both the Upper Bristol Road and the Lower Bristol Road) and difficulties in finding their way around Bath.

The Home Guard and regular soldiers on leave in Bath helped out where they could. The ordinary citizens helped too. Neighbours who were not trapped helped to rescue those who were. Where the rescue proved too difficult for these untrained helpers, they could at least report to the trained Rescue Squads where the survivors were trapped.

When daylight arrived

By dawn on that Monday morning, there were a number of major fires still burning, and ambulances and hospitals were working flat out to deal with the injured.

By dawn on that Monday morning, there were a number of major fires still burning, and ambulances and hospitals were working flat out to deal with the injured.

The Mineral Water Hospital had suffered some damage to one wing, but the remainder was still usable. However, this hospital had been designated a Casualty Clearing Station, and because of the damage, it was unable to fulfil that role.

The Royal United Hospital bore the brunt of the shortfall. According to the hospital records, 147 casualties were admitted to an already overcrowded hospital. When there was no more room in the hospitals for new admittances, patients who could stand the journey were transferred to Gloucester.

Meanwhile the Mortuary Service was trying to identify the dead. The crypt under St James Church which was supposed to be a temporary mortuary, was unusable after the night's bombing, and when the allocated mortuary space that remained undamaged was full, they took over a nearby school. Thus the infants school in Weymouth House in Abbey Green was used as the emergency mortuary.

An unexploded bomb blocked the entrance to Haycombe Cemetery, and that had to be dealt with before burials could take place there. St James Cemetery on the Lower Bristol Road had received several bomb hits, and it too was temporarily unusable.

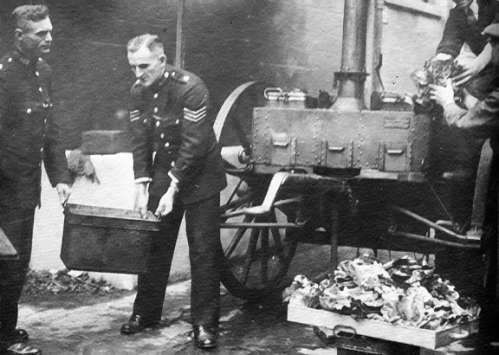

The Rescue Squads continued their work, concentrating at first on those buildings where people were known to be alive but trapped, but finding also some dead or injured to add to the problems of the Mortuary Service, the ambulances and the hospitals. Any valuables found were labelled with the address and sent to the Guildhall for safe keeping. The Home Guard was again stationed at damaged banks and shops selling high value items to prevent looting.

The Rescue Squads continued their work, concentrating at first on those buildings where people were known to be alive but trapped, but finding also some dead or injured to add to the problems of the Mortuary Service, the ambulances and the hospitals. Any valuables found were labelled with the address and sent to the Guildhall for safe keeping. The Home Guard was again stationed at damaged banks and shops selling high value items to prevent looting.

A number of Rest Centres, in particular, the Salvation Army Hostel (picture below, left) and St Bartholomew's Church in Oldfield Park (picture below, right) had been destroyed.

With the loss of these Rest Centres, other arrangements had to be made. Many of the homeless were accommodated in school halls as an emergency measure. It was not unusual for the children who attended school in the next few days to find themselves peeling potatoes or serving meals to those sheltering in the school hall, rather than attending lessons.

As before, the Civil Defence workers worried about the risk of a large numbers of casualties if a Rest Centre was bombed, and set about moving the people using them out of the city, to village halls, army camps or anywhere else considered safe. This was a wise precaution: the pictures below show what happened to the rest centres in the Salvation Army Citadel (left) and St Bartholomew's Church (right). But until the people using Rest Centres had somewhere to go and something to travel in, they stayed in the Rest Centres and needed food and refreshments.

Emergency Arrangements

Six anti-aircraft guns were rushed to Bath and placed around the outskirts to offer some protection in the event of another raid. There was no other raid though and these guns were eventually moved to places that needed them more.

Food

The Ministry of Food rushed in emergency food supplies, which St Martin's Hospital prepared and cooked for distribution to the Rest Centres. As well as those who had nowhere to go except the Rest Centres, those who still had homes and therefore did not need the shelter that a Rest Centre provided, but had no gas or water, could also obtain a hot meal there.

The Ministry of Food rushed in emergency food supplies, which St Martin's Hospital prepared and cooked for distribution to the Rest Centres. As well as those who had nowhere to go except the Rest Centres, those who still had homes and therefore did not need the shelter that a Rest Centre provided, but had no gas or water, could also obtain a hot meal there.

Mobile canteens operated by the Women's Voluntary Service were set up again to serve tea, and the Pump Room became an emergency feeding centre, serving food cooked in Bristol and sent in insulated containers to keep it hot.

The Queen's Messenger Corps arrived in a convoy of lorries: two large tankers of drinking water, two store vans, two mobile kitchens (see picture) and four field canteens. During the day they cooked twelve thousand nourishing meals to feed both residents who could not otherwise obtain food, and members of the emergency services who had come to Bath from elsewhere.

Despite wartime rationing, a total of thirty thousand meals were served during the day and nobody went hungry. Indeed, some people ate better than they normally did.

The Homeless

Those homeless but with somewhere to go, to relatives or friends outside the city, took what belongings they could and set out.

Those homeless but with somewhere to go, to relatives or friends outside the city, took what belongings they could and set out.

To assist this evacuation, those with cars could apply for additional petrol rations.

Extra buses ran from the city centre, though not to any timetable, and large queues built up waiting for each to arrive.

The railway lines around the stations were damaged, but trains were running from Bathampton.

Some just walked. Those who had nothing left to stay for were joined by countless others who had a usable house but just wanted to get away.

Clearing Up

Everyone, and everything was covered in dust.

When very close to an explosion, Bath stone disintegrated into a fine powder. Where houses were damaged, the lath-and-plaster ceilings disintegrated into a mixture of chunks and plaster dust. The mortar between the bricks and stone in many Victorian houses contained a mix of powdered lime and power station waste of ash and coal dust, which rose into the air when a wall was damaged. All this dust was slow to clear from the air, and coated everything.

Householders were encouraged to clear debris and broken glass from their houses as quickly as possible to make them habitable. They were promised that such rubbish, if piled in the front garden, would be collected by the council. It was, but not for many weeks afterwards.

Their other priority was to make sure that no light showed during the black-out times. Torn blackout curtains had to be repaired before lights were used in the rooms behind them.

Soldiers were brought in to help clear roads. Apart from a few unexploded bombs to be made safe, there were roads blocked by fallen trees, telephone wires, bomb craters and collapsed buildings.

The picture below shows New King Street, which was a busy route into the city centre from the west in 1942, and this type of damage, with bomb craters and collapsed buildings was typical of many streets. Rubble from one part of a street could be used to fill bomb craters in another, to create a passable surface.

Most houses were heated by coal fires in 1942, so the lack of gas supplies affected cooking rather than heating. Once windows and roofs were sealed, the house would be dark, but a coal fire would provide both warmth and some light. A burning fire could also be used to cook some foods.

Builders were issued with tarpaulins and timber to make roofs water tight and block up broken windows, so that living spaces could be heated and would remain dry when it next rained.

Identifying The Dead

The other priority was to identify the dead. Some were identified from the address where they were found; some by their identity cards that they had to carry when they were outside their home; some were identified by the survivors who were with them; but some could not be immediately identified.

Lists of names were posted in several prominent places around Bath, so that friends and relatives could check if people reported missing were amongst the dead.

Assessing The Damage

Inspectors from London arrived to assess the bomb damage. There were three reasons for that exercise. Firstly, they wanted to know what types of bomb were used, and in what quantity, so that they could assess the capabilities of the Germans to mount other raids on Britain. They also wanted to know where the bombs fell and how much damage was done, so that the cost of repairing the war damage could be estimated. They also wanted to see how effective the Civil Defence organisation had been, to assess whether any deficiencies had been caused by inadequate Government guidelines or the way they were used locally.

Their report had to be produced very quickly if it was to be of value to the war planners, so their figures were hastily compiled from Civil Defence and Warden reports, rather than seeing for themselves, and neither the bomb count not the location information were completely accurate.

By late afternoon, all the fires were under control and the fire fighters that had come from elsewhere to help had returned to their own fire stations. The Bath fire crews continued to fight the remaining fires until late evening, when all appeared to be out.

When evening arrived

As darkness fell, an enormous number of people set out for the outlying countryside, seeking safety away from any more bombing. According to the Civil Defence records "The number of trekkers was estimated that evening to have risen to about ten thousand, but the exodus was perfectly restrained and orderly".

Most of the Trekkers realised within three or four days after the last bombing raid that Bath was no longer at great risk and they once again stayed in the city at nights. But a few were so traumatised by the bombing that they remained Trekkers for the rest of the war.

If you can't find where you want to go next using the navigation buttons at the top of this page, this button will take you to the page containing the complete site index.